“. . . passenger traffic made the route a paying one from the first day that a passenger coach was attached to the work train, and it is now necessary to carry two passenger coaches and a baggage car to accommodate the people wanting to travel that line.”

The Railroad Comes to the Siuslaw Valley

Today you can get from Eugene to Florence by car in a little over an hour. But in the early 1900s, the journey could take from one to three days using the old stage road, depending on the season. The stagecoach, unlike the ones in the movies about the old west, was basically an open wagon. In bad weather, that meant a long, cold, and wet ride for the driver and passengers.

The Siuslaw River had for decades been the main highway for local commerce, with sailing ships and steam schooners carrying lumber and other products to and from the area. Local businessmen recognized that reliable train service would allow for faster and more dependable shipping of products while also bringing passengers, mail, and staple goods, becoming an important link to the outside world for coastal towns.

The Siuslaw River had for decades been the main highway for local commerce, with sailing ships and steam schooners carrying lumber and other products to and from the area. Local businessmen recognized that reliable train service would allow for faster and more dependable shipping of products while also bringing passengers, mail, and staple goods, becoming an important link to the outside world for coastal towns.

In 1909, a four and a-half foot, clever promoter named William Wilsey, decided to pursue the project and traveled to the east coast to seek investors. But Southern Pacific and its financial backers made certain no one in the United States would touch the project. So Wilsey went to Europe and found a consortium of English investors that were interested. The group sent a railroad engineer named H.A. Sumner to evaluate the project. Sumner confirmed that the project’s prospects were good, but advised focusing on a rail line from Eugene rather than Portland due to potential competition from the larger railroad companies.

At the same time, another group of smaller players led by Isaac Bingham and Ralph Hunt was surveying a line from Eugene to Florence. They too were unable to find American investors, and ended up trying to sell their work to Southern Pacific. However, it became clear that Southern Pacific was stringing them along to see how much progress they had made.

Fortunately, Bingham and Hunt were able to connect with Wilsey, who bought their company and adopted its name, the Pacific Great Western Railway Company. The big railroads didn’t take the new company seriously and assumed it didn’t have the funding or resources to move forward. That meant Sumner was able to buy a 40-acre parcel of land that encompassed the only logical place where the necessary railway tunnel could be built at Noti. Without access to this land, no other company could build a line. Hunt also immediately went to the Siuslaw Valley and began securing properties from local farmers for the necessary rights-of-way.

A Race to the Finish Line

After discovering that the Pacific Great Western Railway Company did have enough funding to build the line, Southern Pacific announced competing plans to build a line of their own from Eugene to Coos Bay. The two companies raced to be the first to Salem to file the papers for the line adoption, and Pacific Great Western won, meaning their line was the only one that could be built. Southern Pacific tried to buy the new company out so they could kill the line, but the directors refused to sell unless Southern Pacific agreed to complete the line as part of the purchase contract. Southern Pacific finally relented, and the project moved forward.

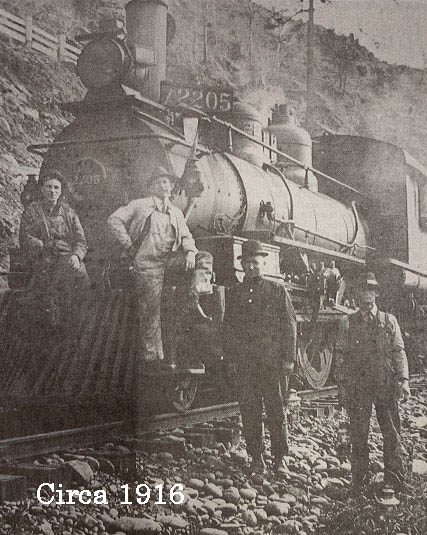

By 1912, there were multiple railroad camps along the new line. The new rail line provided work for local men and a boost to local economies. In Florence and the surrounding areas, local workmen split rails and sold them to Southern Pacific. Farmers supplied food and lumber to the workers who were clearing the right-of-way, building tunnels, and laying the railroad ties.

Passengers to points between Eugene and Florence used the train even before the line was completed. A local newspaper reported that “passenger traffic made the route a paying one from the first day that a passenger coach was attached to the work train, and it is now necessary to carry two passenger coaches and a baggage car to accommodate the people wanting to travel that line.”

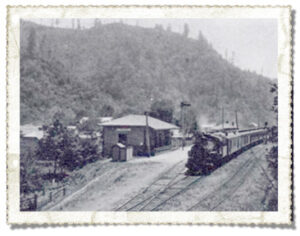

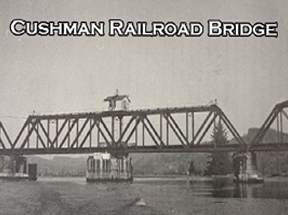

The new rail line began formal operation in 1915. But the line didn’t come all the way to Florence. Instead, it came to Acme, three miles upriver. It then crossed a railroad bridge over the Siuslaw on its way south. Because there was another town called Acme on the Southern Pacific rail lines, the town was renamed Cushman. Passengers traveling to Florence would get off the train at Cushman and travel by wagon or boat to Florence.

The new rail line began formal operation in 1915. But the line didn’t come all the way to Florence. Instead, it came to Acme, three miles upriver. It then crossed a railroad bridge over the Siuslaw on its way south. Because there was another town called Acme on the Southern Pacific rail lines, the town was renamed Cushman. Passengers traveling to Florence would get off the train at Cushman and travel by wagon or boat to Florence.

The Eugene Guard in July 1915 reported that “Florence and the western coast of Lane county are fast becoming a summer resort since the advent of the railroad into the Siuslaw…At Heceta Beach, about three miles from Florence and one mile from the new life saving station, the new resort is growing in popularity.” In August 1915, another local paper reported that “Trains now leave Eugene at 7:20 a.m. and arrive at Cushman at noon. The launches ‘Minnie Mitchel’ and ‘Lena’ carry passengers from Florence and the stage landing and connect with the trains at Cushman.” In fall of 1915, railroad coaches brought an excursion from Eugene and Springfield to Mapleton, where they were met by a fleet of boats from Florence to take them to the 1915 Rhody Festival.

In 1916 the line from Eugene to Coos Bay was completed. The first train made the run in April, for a round trip fare of $3.50. The train stopped at Noti and Mapleton, with additional stops at Cushman, Ada, Canary, and Siltcoos stations. In August 1916, the Eugene Guard reported on a special train to Coos Bay for a three-day celebration of the new line, calling it “the wedding of Eugene Lane and Miss Coos Bay.” The newspaper noted the importance of the coastal towns, including Florence, Mapleton, and Acme, to the future development of the state of Oregon. It attributed the importance to “the enormous resources yet undeveloped, the wide areas of territory yet open for settlement, and the commercial relations yet unpromoted.”

Within three years of completion of the line to Coos Bay, demand was so heavy that a sleeper car was added. Ridership continued to grow and at times even exceeded the trains’ capacity. In 1919, the local newspaper reported “The train was so full this afternoon that 40 men made the trip in the baggage car.”

With the increase in travelers and frequency of trips, stations along the line became thriving communities that benefited from tourist dollars and a flourishing local timber industry. In the 1920s, Florence continued to receive passengers, freight, and mail from Cushman via boat. Commerce continued with freight trains leaving the Florence area loaded with lumber products, produce, and other shipped items. However, over the next few decades, the completion of the coastal highway and introduction of the modern automobile reduced the number of passengers. In June of 1953, after 36 years of daily round trips from Eugene to Coos Bay, the train made its final passenger run.

With the increase in travelers and frequency of trips, stations along the line became thriving communities that benefited from tourist dollars and a flourishing local timber industry. In the 1920s, Florence continued to receive passengers, freight, and mail from Cushman via boat. Commerce continued with freight trains leaving the Florence area loaded with lumber products, produce, and other shipped items. However, over the next few decades, the completion of the coastal highway and introduction of the modern automobile reduced the number of passengers. In June of 1953, after 36 years of daily round trips from Eugene to Coos Bay, the train made its final passenger run.